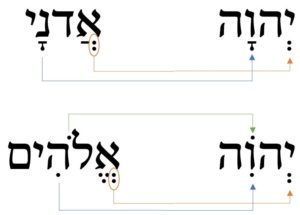

When the question of the pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton comes up, we are generally told by those “in the know” (and, honestly, in the right) that the vowels written on יְהוָֹה belong to the name אֲדֹנָי and serve as a visual reminder for us to read יְהוָֹה as ʾăḏōnāy rather than attempting to sound it out mark-for-mark. This is the standard explanation that you will receive from a beginning Hebrew grammar or from any standard lexicon. Thus, Seow (1995) explains this by saying that “[i]n the Hebrew Bible, the vowels of the word אֲדֹנָי ‘my Lord’ are superimposed on the four consonants (thus, יְהֹוָה or יְהוָה)” (p. 61). Unfortunately, he gave no explanation as to why the composite sheva (םֲ) was written as a simple sheva (םְ) on the Tetragrammaton, and most explanations have lacked explanatory force for many people (especially for those who are less adept at reading Hebrew).

Seeing this change of sheva (and the lack of cholam on the Tetragrammaton, while somehow overlooking its absence from the word אֲדֹנָי), some have come to a different conclusion. These dissenters tend to point out the obvious truth that the exact vowels of אֲדֹנָי (םֲםֹםָ or ă.ō.ā) are not present on יְהוָֹה (םְםֹםָ or ə.ō.ā), since the former has chataf-patach (םֲ or ă) in the first syllable, while the latter has a simple sheva (םְ or ə) in that syllable. This is patently obvious to anyone who will be look at the words, and it was expressed straightforwardly in the following:

The first thing which I saw, on opening my eyes, was that יְהוָֹה has not the vowels of אֲדֹנָי. It has only two out of three. The excuse that םֲ is written as םְ because it is under י evidently will not hold; for, on the hypothesis that the vowel points of יהוה are a q’rey perpetuum of אֲדֹנָי, the םְ is to be read, not with י, but with א, which is impossible. Where the Maçoretes intended יהוה to be read as אֱלֹהִים, they put the vowel points of that word, notwithstanding that םֱ fell under י, and who can doubt that they would have put the vowel points of אֲדֹנָי to יהוה, if they had intended by these vowel points, to indicate that it was to be read as אֲדֹנָי? (Levy, 1902, p. 98; ם used here to hold vowels not in original)

Nehemiah Gordon (2003) expressed the same concern and concluded that “with the vowels of Adonai it should have been Yahovah יֲהוָֹה” rather than Yehovah יְהוָֹה (p. 3), and he makes this point explicit in his video presentation (Gordon, 2014), in which he states clearly that every single mark of the word that is supposed to be written is placed on the word that actually sits in the text. This is an clear mistaken on his part, however, as will be demonstrated now.

וּבַטְּחֹרִים – Gordon’s Mistaken Argument

The Masoretes (a group of scribes who lived and worked between the sixth and the tenth centuries of the common era) had as their goal the preservation of the consonantal text that they had received as their tradition. We have recorded a few instances in which the scribes before them had altered the consonants of the text (see Emendations of the Scribes), but the Masoretes would not themselves alter anything that existed in the Bible.

However, the biblical text contains mistakes. Some words are spelled wrong. Some are unclear. Some don’t sound good to the ear. In any place where the Masoretes thought that those who read the Bible in public (for religious services) should change what was written in the text, they did not change the text itself. Instead, they added a note in the margin with the word that should be read (which they called by the Aramaic term קֱרִי qĕrî [pronounced kri]) and placed the vowels of that word on the word that is actually written in the text (which they called by the Aramaic term כְּתִיב kəṯîḇ [pronounced ktiv]). The system is called קֱרִי וּכְתִיב qĕrî ûḵĕṯîḇ by Hebrew speakers today.

In the Bible this system normally displays a transfer of the complete vocalization of the kri onto the letters of the ktiv. For example, in Deuteronomy 22:15 (and throughout the chapter), the author wrote the word נער (which is, to us, a masculine word נַ֫עַר “young man”) when he clearly was referring to a young woman (נַעֲרָה). The Masoretes wrote the vowels of the feminine form on the letters that appear in the Bible, so that they wrote הַנַּעֲ֯רָ (the definite form) with the little circle (called a “Masorah circle”) to tell the reader to check the margins for a comment. In the margin, they wrote נערה ק̇, telling the reader that what is read (ק̇ = קֱרִי) is נערה with the vowels that are found on the word in the text (that is, נֲעֲרָה). This is illustrated in the image, to the right, of the relevant verses in the Leningrad Codex.

Deuteronomy 22:15

וְלָקַ֛ח אֲבִ֥י הַֽנַּעֲ֯רָ֖ וְאִמָּ֑הּ וְהוֹצִ֜יאוּ אֶת־בְּתוּלֵ֧י הַֽנַּ֯עֲרָ֛ אֶל־זִקְנֵ֥י הָעִ֖יר הַשָּֽׁעְרָה׃

ק̇ הנערה

Gordon (2014) gave the example of the kri ובטחרים having its vowels written on the ktiv וּבַעְפֹלִים at Deuteronomy 28:27 (beginning at time marker 1:11:15). On the basis of this (and similar cases), Gordon argues that we should expect a complete transfer of the chataf-patach from אֲדֹנָי to יֲהוָֹה, but we don’t have this in the manuscripts. Instead, it would seem that the composite sheva (םֲ) is written simply as a sheva (םְ). This is indeed problematic and seems to contradict what we see in all other instances of the ktiv-kri system, but let’s take a closer look at the verse in question. Here is the text as it comes from the Leningrad Codex:

Deuteronomy 28:27

יַכְּכָ֨ה יְהוָ֜ה בִּשְׁחִ֤ין מִצְרַ֨יִם֙ וּבַעְ֯פֹלִ֔ים וּבַגָּרָ֖ב וּבֶחָ֑רֶס אֲשֶׁ֥ר לֹֽא־תוּכַ֖ל לְהֵֽרָפֵֽא׃

ק̇ ובטחרים

Gordon, however, overlooks the mistake in this specific example that he gives. The kri (ובטחרים) requires a dagesh in the tet (טּ) by the rules of Hebrew grammar, and that dagesh is not in the ktiv (וּבַעְפֹלִים). The corrected form would be וּבַטְּחֹרִים, but using the system to take the vowels exactly off of וּבַעְפֹלִים, we get וּבַטְחֹרִים (without dagesh in the tet), which is a grammatical mistake. It cannot be this way. Yet, it is Gordon’s argument that every mark of the kri is present on the ktiv. If that were the case, we would see וּבַעְּפֹלִים in the ktiv. Since ע naturally rejects dagesh, it is not included in the ktiv form.

Thus, the very example that Gordon gives to undercut the position of nearly all Hebrew teachers serves to disprove his contention. Because the ktiv lacks the dagesh, it does not represent every mark which the kri requires to be grammatically correct. In fact, the same way that the ayin rejects dagesh (and this is the justification for its omission in the ktiv), the yod naturally rejects composite sheva (and this is also the justification for the change from chataf-patach in ʾăḏōnāy and chataf-segol from ʾĕlōhîm to simple sheva when these vowels are transferred onto the Tetragrammaton).

Transference of Vowels to Ktiv

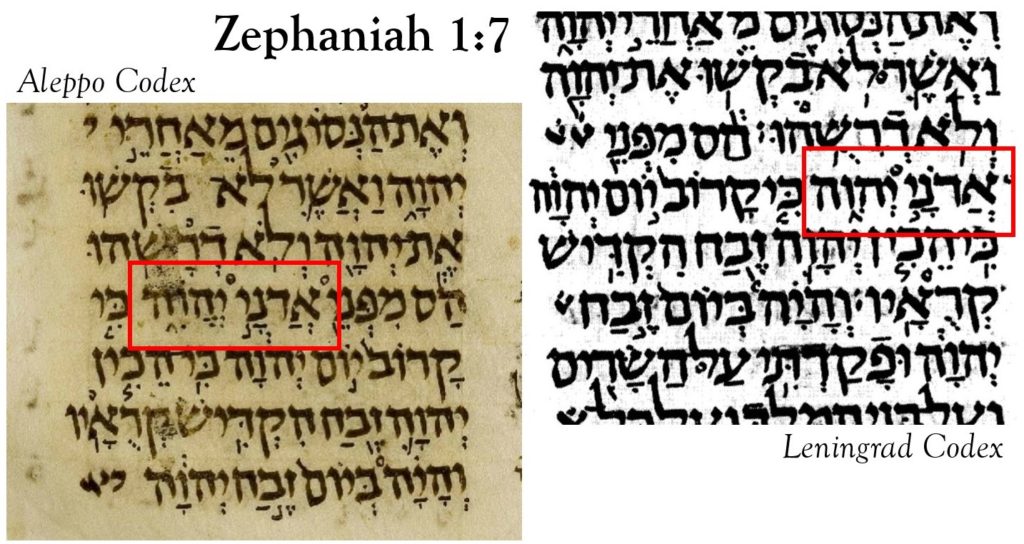

At this point, we should recall what we saw from Levy (1902) above, where he argued that if the Masoretes had intended to transfer the vowels of אֲדֹנָי onto יהוה, they would have written יֲהוָֹה rather than יְהוָֹה (p. 98, quoted above). This is simply not true, however. When the Masoretes expected the Tetragrammaton to be read as אֱלֹהִים, they vocalized it as יְהוִֹה (in the Aleppo Codex) or as יְהוִה (in the Leningrad Codex). The Aleppo Codex has only one instance in which it is pointed with the chataf-segol (יֱהוִֹה), at Zephaniah 1:7, which the Leningrad Codex points in the regular way as יְהוִה.

The pointing of יהוה with the vowels of אֱלֹהִים occurs 280 times in the extant Aleppo Codex. In every instance except for Zephaniah 1:7 (in the image below), the chataf-segol is transferred to the Tetragrammaton without the segol (only as sheva). This is precisely what is done with the transference of the vowels of אֲדֹנָי to יְהוָֹה—one-for-one! In fact, the Aleppo Codex has 367 clear instances of אֲדֹנָי marked with kamats (that is, אדני as a name of God). In 356 of these (that is, 97% of instances), the cholam is missing from the word (as in the image to the right). This explains the lack of cholam on the Tetragrammaton. Since it was not written on אֲדנָי, it was not written on יְהוָה. It is a one-for-one transference of the vowels from the one to the other.

Every piece of evidence that we have indicates that the vowels of אֲדֹנָי are placed on יהוה in normal circumstances, just as the vowels of אֱלֹהִים are placed on יהוה when it follows אדני (that is, as אֲדֹנָי יְהוִֹה).

יְהוָֹה יְהוָה יְהוִֹה יֱהוִֹה יְהוִה יהוה

The name of God is written and vocalized in several different ways. The Dead Sea Scrolls contain evidence of the use of Paleo-Hebrew letters within otherwise square text (something similar to: וידבר יהוה אל משה “and Yhwh spoke unto Moses”). Sometimes it was written with a cholam; other times it was missing. Sometimes it had a kamats in the final syllable; sometimes a chirik. Sometimes it has a chataf-segol in the first syllable; most of the time, it has a sheva. The task at hand is to be able to explain the diversity of forms and how we arrived at them—to understand all of the possibilities and successfully justify each unique combination. Assuming that יְהוָֹה is the original form gets us nowhere in that endeavor. There is nothing to prohibit us from reading אֲדֹנָי יְהוָֹה as ʾăḏōnāy Yəhōvâ. If these are the vowels of the name, there is no necessity that would have driven the Masoretes to write אֲדֹנָי יְהוִֹה instead, except in the case that יְהוָֹה was actually being read as ʾăḏōnāy and the change of vocalization was intended to prevent us from reading ʾăḏōnāy ʾăḏōnāy (thus, changing the second instance to be read as ʾĕlōhîm).

As it is, we can draw certain conclusions about the habits of the scribes of the Aleppo Codex and the Leningrad Codex with regard to their treatment of the Tetragrammaton.

The scribe of the Leningrad Codex pointed אֲדֹנָי ʾăḏōnāy with all of its vowels. However, he left the cholam off of יְהוָה just as we see it in the Aleppo Codex. When the Tetragrammaton was to be vocalized like אֱלֹהִים ʾĕlōhîm, he again left the cholam off and wrote יְהוִה. This was his consistent pattern. He left the cholam off of the Tetragrammaton as a regularity.

The scribe of the Aleppo Codex, however, pointed אֲדֹנָי ʾăḏōnāy without the cholam as אֲדנָי. These vowels are what we find represented by יְהוָה (which follows it in dropping the cholam). However, when it was to be vocalized like אֱלֹהִים, he included the cholam and wrote יְהוִֹה because he never left the cholam off of the word אֱלֹהִים.

These patterns are consistent, although none of the patterns is one hundred percent. Randomly, a scribe might include the cholam on one form where he would usually exclude it. He might write a chataf-segol where he normally writes a sheva. These aberrations are random and cannot be exhibited as intentional by comparison of the manuscripts. Thus, discovering that cholam appears at random points within the manuscripts should generate no excitement in the researcher. As said, three percent of instances of אֲדֹנָי have the cholam in the Aleppo Codex. It’s something that is bound to happen, and the same is true with the Tetragrammaton. It appears some times with cholam, the full pointing of the word from which it drew its vocalization.