Jonathan brought to my attention a couple of days ago that we haven’t done any real kind of update about our activities recently. The last post I made about this was back in February. So, I’m going to write really quickly now to let you know what we’ve been doing and working on around here. Also, I’d love it if you gave me some feedback about new things you’d be interested in doing.

It’s been our recent practice to divide our sessions up into “first hour,” “second hour,” and “third hour,” as we do three hours on Monday evenings. These hours are 5:00pm, 6:00pm, and 7:00pm (Eastern US), which correspond to 12:00am, 1:00am, and 2:00am in Israel. I know that this isn’t a convenient time slot for everyone in the world, but I’m not sure what else I can do at this point.

First Hour — Reading Hebrew

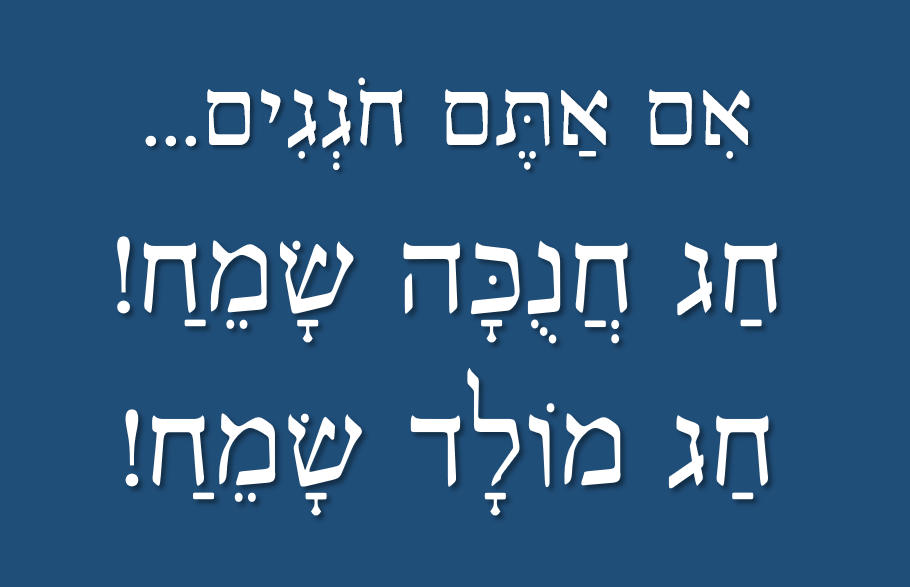

Since Simḥaṯ Torah, we’ve been reading through a single aliyah from within Parashat haShavua [פָּרָשַׁת הַשָּׁבוּעַ Pārāšaṯ Haššāḇû(a)ʿ]. Our reading schedule is posted online here.

Second Hour — Translating into Biblical Hebrew

Until now, we’ve been using the second hour to translate from KJV-style English into biblical Hebrew using Weingreen’s Classical Hebrew Composition (Oxford, 1957).

Third Hour — Modern Hebrew (now using Hebrew from Scratch, book 2)

Colton and I have been going through a set of textbooks intended to introduce students to spoken Hebrew. It’s been a great ride, and Colton has made great strides. We’re very willing to review and practice speaking if anyone wants to join us!

Anyone who makes a paid subscription on Patreon can join us on Stream and join the modern Hebrew hour.

To check out our past and upcoming streams, go to The Hebrew Café’s YouTube channel under the Live tab.