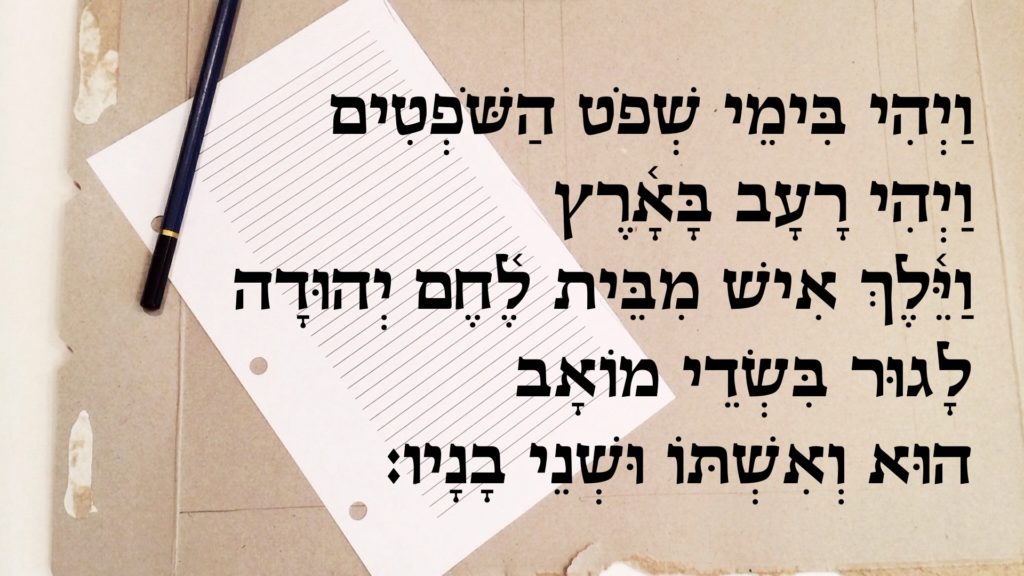

Image: Ruth 1:1 (Masoretic Text)

Above is the text of Ruth 1:1, as we look at the introduction to this fantastic book of the Hebrew Bible. In Jewish circles, people tend to call it Megillat Rut (מְגִלַּת רוּת), the “scroll of Ruth,” rather than the “book” of Ruth. This is because Ruth is written on a separate scroll that is publicly read during the holiday of Shavuot (חַג שָׁבוּעוֹת), just as Lamentations (אֵיכָה) is read during the night of Tisha Be’Av (ט׳ בְּאָב) to commemorate the two-time destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem.

For those who are interested in a linguistic treatment of the text, you will certainly be challenged by Robert D. Holmstedt’s Ruth: A Handbook on the Hebrew Text (Waco, TX: Baylor UP, 2010). I recently purchased a copy, and it has renewed my passion for this book of the Bible.

The workbook to Karl Kutz and Rebecca Josberger’s Learning Biblical Hebrew: Reading for Comprehension (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2019) contains the entire text of the book with vocabulary helps for beginning readers.

Let’s look at what’s contained in this first verse and break it down. I’d like to start this as a series.