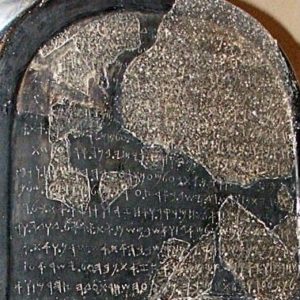

Emerging from the Canaanite milieu of Semitic languages, Hebrew has been around for a very long time. It isn’t clear how old the language is, but most place its emergence in the early second millennium before the Common Era (just before 1,000 bce). The language was actually called at one point in the Bible “the language of Canaan” (שְׂפַת כְּנַ֫עַן; cf. Isaiah 19:18), and we see from inscriptions from the early period of the language that several other Canaanite languages (such as Moabite, Ammonite, and Edomite) were very close to Hebrew in orthography (the alphabet that they used), in lexical stock (the words themselves), and in accidence (grammar, morphology, and syntax). Anyone who is trained to read the Siloam Inscription in Hebrew will be equally equipped to read the Mesha Stele in Moabite, even though these are technically different dialects of Canaanite language. These languages were certainly mutually intelligible by native speakers of each from that period.

If we draw a line between Moabite and Hebrew as distinct languages, though they were so very similar, what do we make of modern and biblical Hebrew? Are they essentially the same language? Should they be classified as distinct languages? Can learning modern Hebrew be at all advantageous to a student of the biblical language? Or, should those who aspire to master the language of the Bible avoid contaminating their thinking by adopting modern Hebrew?

If we draw a line between Moabite and Hebrew as distinct languages, though they were so very similar, what do we make of modern and biblical Hebrew? Are they essentially the same language? Should they be classified as distinct languages? Can learning modern Hebrew be at all advantageous to a student of the biblical language? Or, should those who aspire to master the language of the Bible avoid contaminating their thinking by adopting modern Hebrew?

These are the concepts that I would like to explore a bit in this blog post.

Continue reading “Are Modern and Biblical Hebrew Distinct Languages?”